Article content continued

To reduce that friction, the Public Health Labs, under Allen, have been buying exclusively non-proprietary instruments since February. That allows them to mix and match supplies for different parts of the operation from different suppliers, some of them domestic. But the so-called open systems just aren’t as powerful as the best proprietary machines. A single, open-system instrument, fully stocked and staffed, can only process 1,854 samples in a day, just over half what the Roche machines can do. “When we do have reagents (the Roche machines) are phenomenal workhorses,” Allen said. “So we’re not ready to abandon them entirely.”

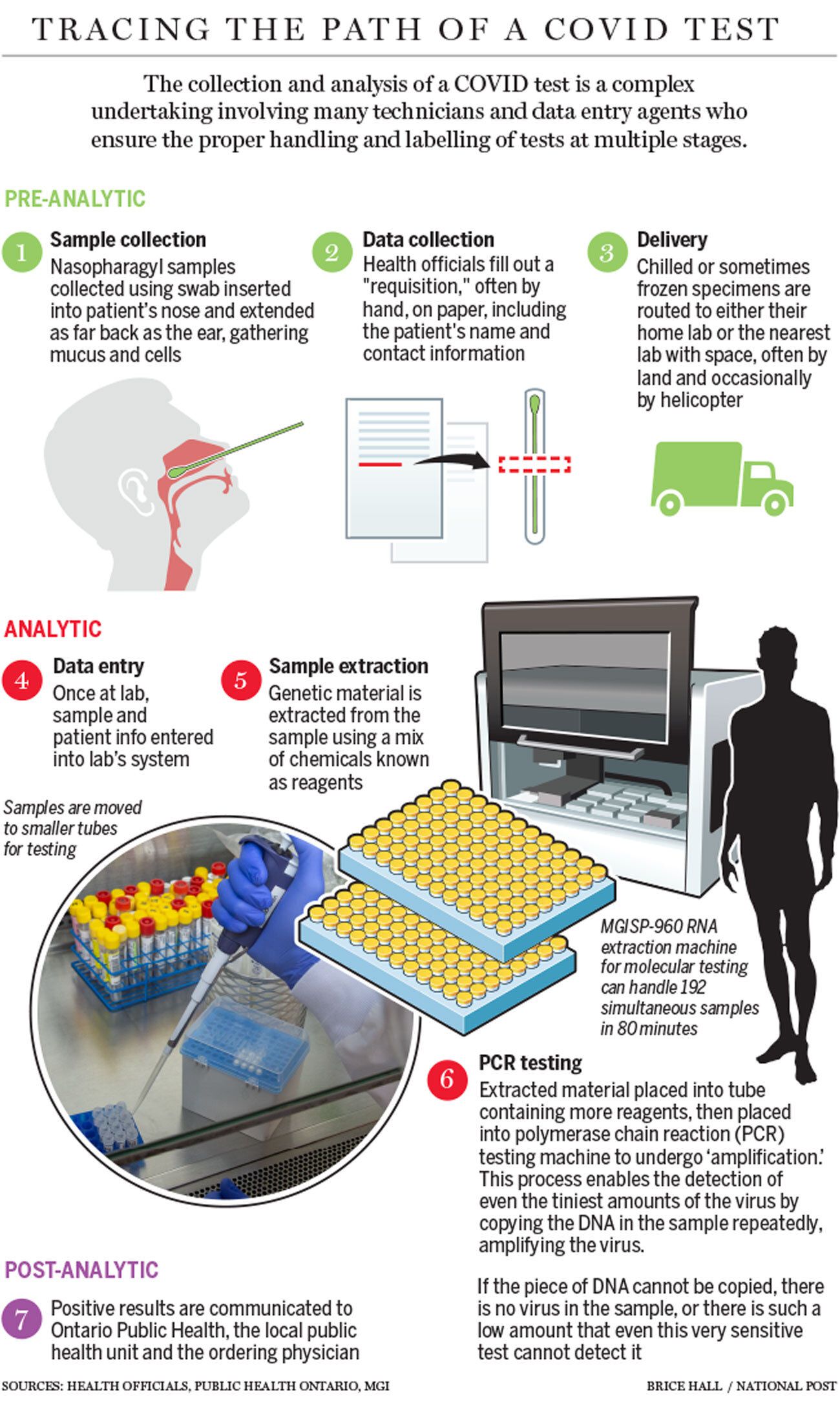

Staffing, too, has been a constant problem. A molecular PCR test is not a simple procedure. It’s not like a pharmacy-bought pregnancy test. It takes real expertise to both conduct and interpret.

Most of that work has to be done by licensed laboratory technologists. But since at least the 1990s, Ontario has had a severe shortage of those kinds of techs. The issue, according to Michelle Hoad, the chief executive officer of the Medical Laboratory Professionals Association of Ontario, goes back to a decision made in the 1990s to close seven of the province’s 12 programs for training technologists. At the time, she said, there was a view that as lab processes got more automated, fewer humans would be needed to work in each lab. But it hasn’t worked out that way.

Garth Riley, who retired as the director of Ontario’s Public Health Labs in 2015, said that issue was known and talked about at the highest levels of the organization for most of his tenure there. “And it still hasn’t been addressed properly in my opinion,” he said. There have been more recent warnings, too. For the last 18 months, Hoad and her colleagues have been meeting with the government, trying to get them to do something about it. “I don’t think it was taken as seriously as it should have been,” she said. “And then COVID hit.”