Article content continued

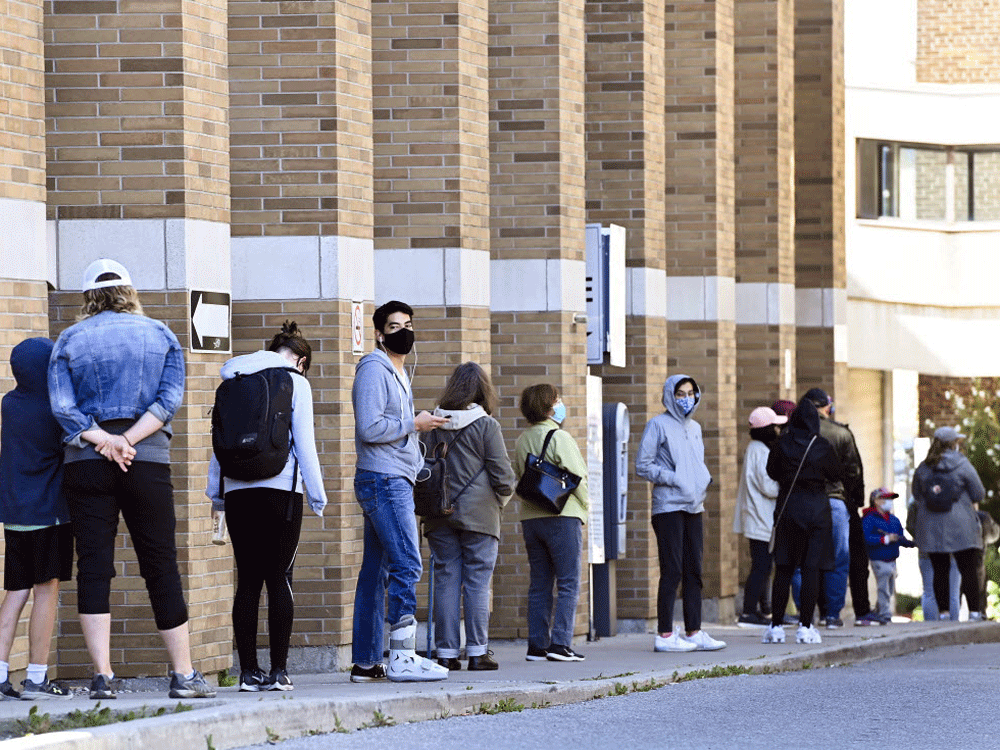

Until rapid, cheap tests are approved by a federal government that appears in no great hurry to do so, the priority must be people with symptoms and those who have had significant exposure, experts say. “By flooding the system with asymptomatic testing, we jeopardize that response,” says McMaster University infectious diseases specialist Dr. Dominik Mertz. The more bottlenecks, the longer the turnaround times for results, the longer the delay in reacting to a positive test.

Alberta will still be offering asymptomatic testing of high-risk groups, including health-care workers, teachers and staff, people living in long-term care and the homeless.

B.C.’s provincial health officer, Dr. Bonnie Henry, has resisted testing people with no known symptoms or known contacts, arguing the evidence doesn’t support it.

Some say we need to de-emphasize the focus on daily numbers. The current gold-standard swab test used to detect viral RNA, a sticky molecule, can remain positive for weeks after infection. It doesn’t necessarily mean the person is still infectious.

The person who has no symptoms who has really been good … the probability we’re going to find out they’re positive is going to be extraordinarily low

Dr. Irfan Dhalla wants more emphasis on the numbers of cases with an unknown source of transmission, the proportion of tests completed in less than 24 hours, and how many contacts identified each day and contacted within 24 hours of identification. In Ontario the source of exposure is “unknown” in about 40 per cent of cases, “so clearly the test, trace, isolate system isn’t working as well as it could,” says Dhalla, of Unity Health Toronto.